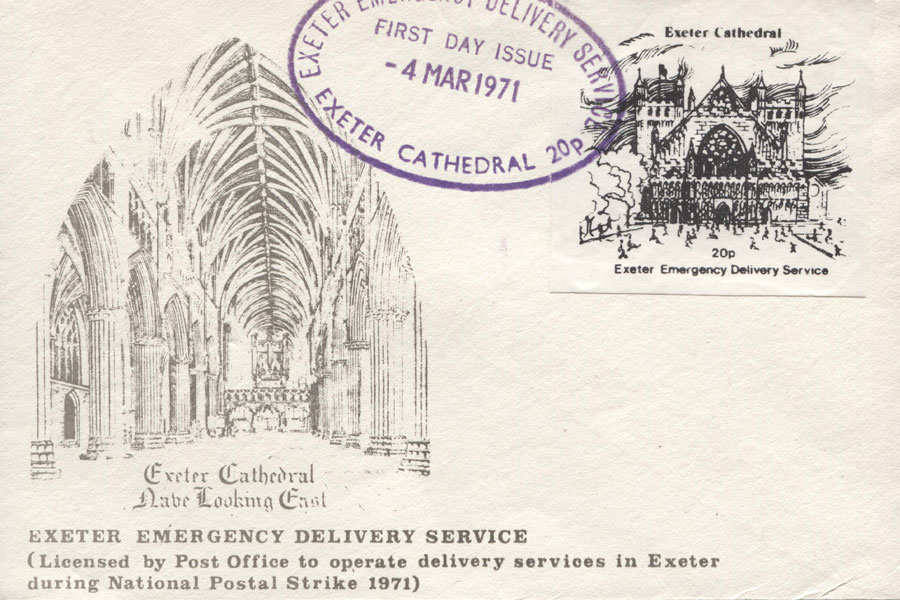

Thankfully, these days, we do not see or hear of many workers’ strikes in the UK but back in the 1970s and 1980s they were certainly more commonplace, and one of the more “infamous” disputes was when 200,000 postal workers walked out exactly 50 years ago in 1971.

Late in 1970 the Unions had asked management for a minimum rise of £3 per week which represented a 15-20% increase. Today, that sounds like an astronomical request, but in context, at the time inflation was running at 10% and so in the circumstances was not too unreasonable. Management made an offer of 8% on the 14th January 1971 which was rejected and so workers went on strike on the 20th. The strike lasted for 7 weeks with pretty much 100% coverage of all towns, cities, and rural villages. Some Post Offices did open their doors for a few hours a week so that pensions and other benefits could be collected but all in all it was one of the largest national strikes ever seen in this country. Given the importance of our Post Offices today with all the varied services they offer, and the amazing work that our Postmen and Postwomen do every day, it would be a major disaster if a similar action were to take place in these times.

In the end, the Unions had to back down as they had run out of money. Financially supporting in the region of 30-40,000 workers, who had no income during that 7 week period, was an enormous strain on the Union’s coffers and so all workers returned to work on the 8th March 1971.

However, as far as the stamp collecting fraternity were concerned, this disruptive period produced a wealth of fascinating stamps and envelopes that we are still learning about today. Unlike now where we seemingly have hundreds of courier companies delivering letters and parcels, in 1971 the Post Office and Royal Mail, which was all one group then, had a virtual monopoly. In the early days of the strike, it was very clear that neither side was going to back down very easily and so this worsening situation for both the public and, but perhaps more importantly, businesses, led to numerous small companies setting up their own local delivery companies. These private enterprises took advantage of the increasing demand and operated mainly in towns and cities across the country. Due to the lack of manpower and transportation, these services tended to be operated solely for the purposes of the town or city that they were in, but even so, it became a valuable lifeline for many people. But how do you prove that the customer has paid for the delivery service? – well, you issue stamps of course! And so it was that this national crisis spurned many thousands of different stamps that were locally produced and actively collected by philatelists. Whilst the majority of issues from hundreds of different companies are known to collectors, we are still discovering “new” items 50 years later! In a way this is the reason why many collectors steer well clear of this area. Unlike when the Royal Mail issue stamps, whereby they are completely transparent and accountable on how many stamps have been sold for each issue, the companies producing private labels had no legal reason to disclose quantities of stamps that they had printed and subsequently sold. Collectors need to be reassured with the knowledge that when they are buying stamps that they are getting value for money. In this case, with the 1971 Strike Mail stamps, it is very difficult to know what “good value” is for two reasons. Firstly, collectors can normally turn to catalogues and collector-based books/articles to discover approximate market values, which tend to be loosely based on quantities printed. However, mainstream catalogues will not list these Private Strike Mail labels or similar stamps from around the world, because they were not produced by the official postal administrations and so were essentially “illegal” stamps. Most stamp collectors will only collect official stamps from their chosen area and so these unofficial stamps tend to have a much smaller following. Secondly, as mentioned earlier, the scarcity of these issues will always be up for debate due to the unknown quantities printed and sold. Let us imagine that the National Postal strike is 6 weeks in, and we are a small courier company working in a town delivering local letters and parcels and business is very brisk. With the end of the strike not in sight we decide to print 5,000 more stamps to satisfy the demand. We get through 500 when the strike finishes. What do we do with the remaining 4500 that have been paid for and are sitting in our office? Do we destroy them? Or do we keep them, seeming as we have spent good money on them and after all, there may well be another strike in a month’s time. The chances are they would have been kept, but eventually forgotten about, gathering dust in some cupboard. This is the collector’s dilemma. At first glance this stamp could be quite scarce and collectable as only 500 were issued and many of those may have been destroyed if the recipient of the letter or parcel was not a stamp collector. However, there are 4500 sitting in a room which could be released onto the market in a year, a decade, or even 50 years or maybe never. So, although this period in UK philately is fascinating and still very much under researched, the number of specialists is very small and consequently the old adage “supply and demand” means that prices will always appear low given that there is only a tiny fraction of Strike Mail stamps existent compared to mainstream Great Britain issues.

Whether it was a coincidence or just bad luck, the period of the strike encompassed one of the biggest changes in our financial system. £sd or Pounds, Shillings and Pence had been in use for hundreds of years but come February 15th, 1971, we went “Decimal”. 100 new pence equalled £1. Even though this was planned years before, it was still to be a seismic change for the public and affected all aspects of life – whether buying groceries, stamps, paying your bills, wage packets, coins in your pocket, it would take a lot of getting used to. The strike caused a “limbo” in the stamp world. New stamps were already in production way before the strike was even muted and thousands of collectors were excited about the historical new issue and looking forward to the 15th February, when they could at last purchase their stamps and obtain a First Day Cover. Except they could not – the strike put paid to that. Even though many First Day Covers were produced “en masse” beforehand they could not be delivered on “Decimal Day” and so collectors had to wait until the strike finished when at last their cherished covers could be received. It has always been quite common for postal services around the world to supply a reason for late delivery of a large quantity of mail. It maybe due to a fire in a delivery office, or a mail train crash or a postal bag placed on the wrong plane, and this 1971 strike was no different. All Post Offices were instructed to mark all the 15th February First Day Covers with the “POSTING DELAYED BY THE POST OFFICE STRIKE 1971” handstamp as seen below. This type of “Decimal Day” cover is only worth a pound or two due to the vast quantity produced but it remains a great record of this historical event.